The group, founded by two Filipina American sisters, was praised by David Bowie and has been cited by artists like Bonnie Raitt and the Go-Go’s as a major influence.

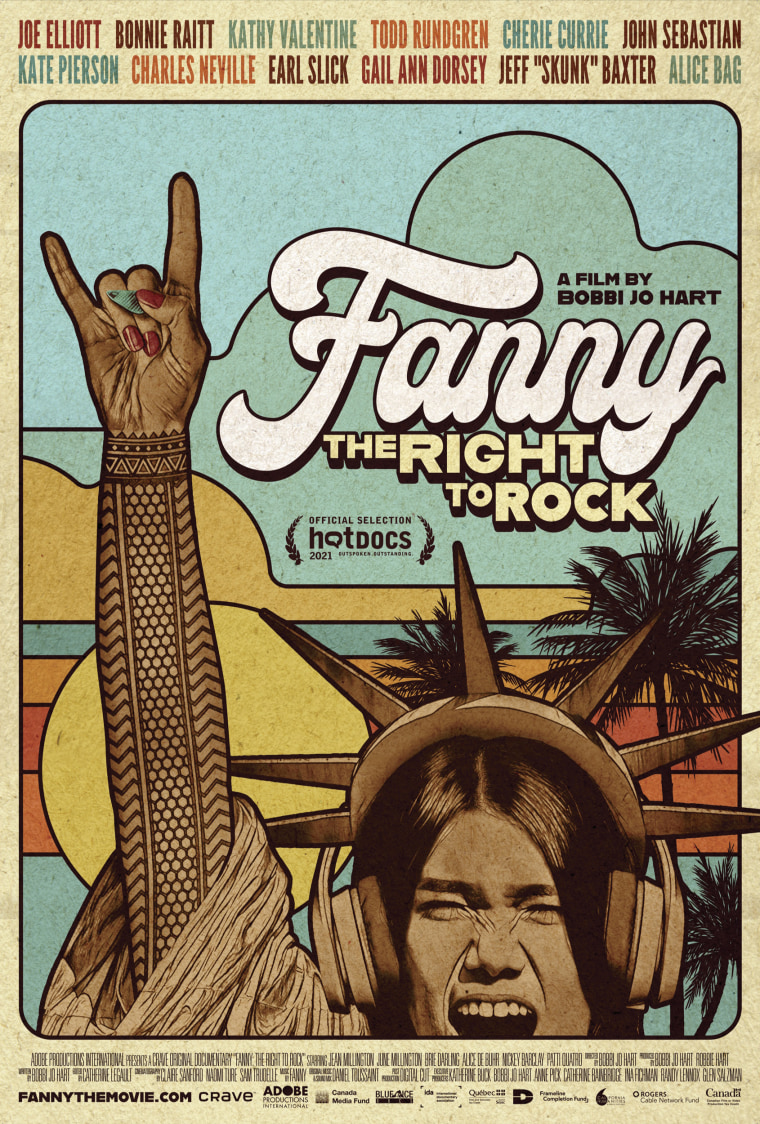

Founded in California by June and Jean Millington, sisters born in the Philippines to a Filipino woman and an American naval officer, Fanny is still hailed for its songwriting and melodies, and counted some of the biggest stars of the day as fans. A new documentary “Fanny: The Right to Rock” aims to put the band in its rightful place in music history by tracing its origins in the Philippines through its rise to fame, to the recent reunification of many of the band’s early members. Among the stars who cite Fanny as a major artistic influence in the film are Bonnie Raitt, the Go-Go’s, The Runaways and Todd Rundgren.

The film is currently on the film festival circuit and is screening as part of the San Diego Filipino Film Fest on Oct. 14; the OUTShine Film Festival in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, on Oct. 16; and as part of the Seattle Queer Film Festival on Oct. 23.

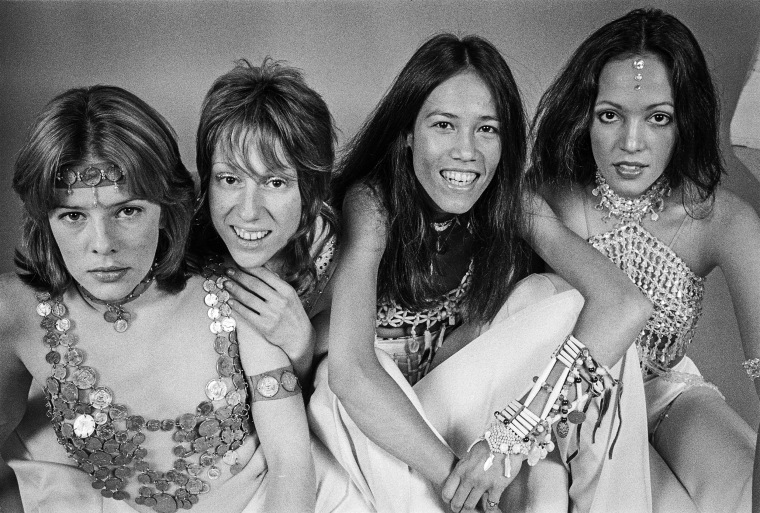

As the film shows, no one was more surprised that rock music would bring a group of young Asian American women together than the band members themselves. An early iteration of the band consisted of June Millington, who sang and played lead guitar, and Jean Millington, who played bass; fellow Filipino American Brie Darling on vocals and percussion; keyboardist Nickey Barclay; and drummer Alice de Buhr, who were all still in their teens at the time. (Barclay and de Buhr are white.) Darling, the child of a former military officer and a Filipina immigrant, remembers how excited she was when she heard the Millingtons were searching for a drummer.

“One of them played bass, one of them played guitar, they were my age, and we were exactly the same racial mix,” Darling, 72, said. “When I found out they were looking for a drummer — I think my mom read it somewhere — it was a perfect mix.”

However, the pressures to conform to the demands of the industry and fans nearly derailed the band several times. The members of Fanny chafed at the industry’s attempts to give the band a highly stylized image that required extremely feminine outfits and a commitment to conformity. Darling, who married at 17 and had a child three years later, was asked to leave the band both because of her pregnancy and because the label wanted the band to have four members to mirror the Beatles. For the queer members of the band, like June Millington, there was also an awareness that the industry would prefer that they stay in the closet.

“There was a sort of secret ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ policy that was unspoken and with me my whole life. If somebody had asked me, I would have talked about it, but nobody did,” said Millington. “But that 'don’t ask, don’t tell' policy was with me my whole life. We couldn’t talk about being Filipino. Why? Because people didn’t want to see it. We couldn’t talk about racism or sexism.”

But despite those obstacles, Fanny would get the attention of the male dominated world of music criticism at the time, with many writers noting the high bar an all-woman band had to clear. “A male group playing as well would have gotten standing ovations from the Fillmore audience,” a critic for The New York Times wrote in 1971 after a show at the legendary San Francisco venue.

Millington recalled how the band was often greeted with boos and jeers by crowds that did not know what to make of a group of primarily Asian American women playing rock music. While those shows would get off to awkward starts, the band prided themselves on their ability to turn things around. “We did not feel racism when we were playing music,” said Millington. “It’s really incredible. People didn’t fight about race while dancing.”

Darling notes that one of the reasons she did not resent audiences for not understanding more about her experiences as a mixed race Asian American woman was because of the tumult of the 1960s and '70s and the struggles most communities of color faced at the time. After leaving Fanny, Darling pursued a career in acting, but quickly realized that casting agents didn’t know what to make of her. “They didn’t know what I was at the time. But a lot of African Americans were also not getting work on TV. So why would a Filipino be recognized?” she said.

That outlook also affected the way she and her bandmates viewed booing audience members in the earliest days of the band.

“If somebody looked at me as if they weren’t expecting much or if, you know, they weren’t particularly friendly,” Darling recalled, “I just thought to myself, ‘Just wait until we play. Wait until you see what I can do.’”

Written by Lakshmi Gandhi for NBC News.

Comments